Visited by ODOjack & tour group on the 24th February 2019

For nearly 90 years a single train left a dedicated station once a day and travelled non-stop for 40 minutes until it reached its passengers’ final destination – Brookwood Cemetery.

Welcome aboard the London Necropolis Railway.

The Necropolis Railway

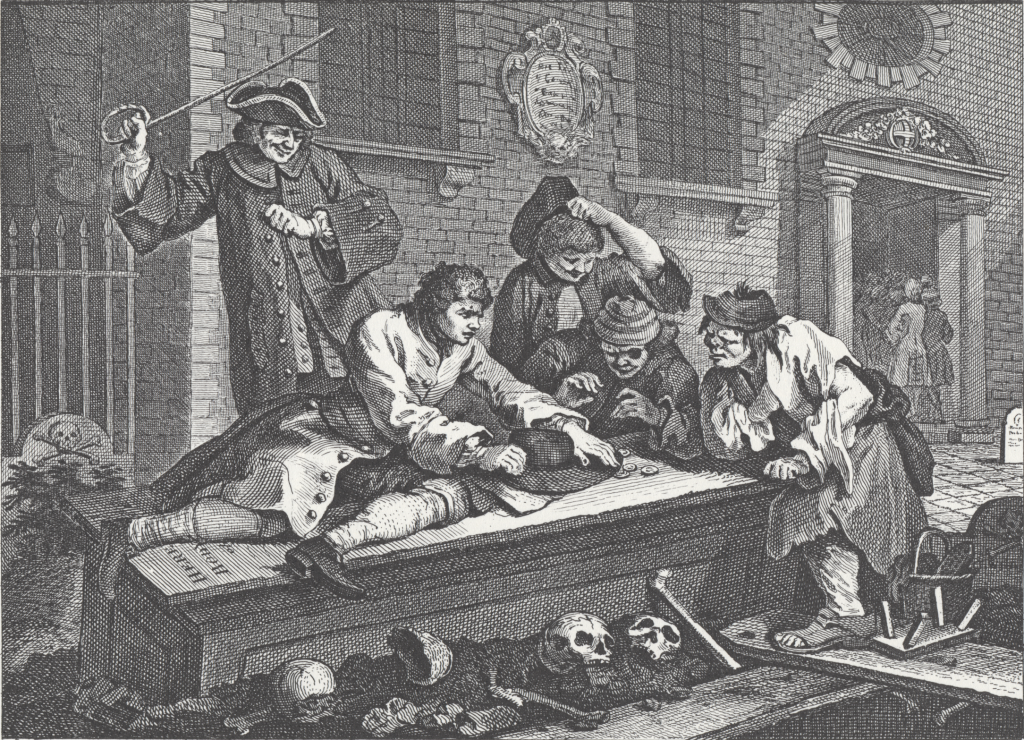

London’s population more than doubled in the first half of the nineteenth century, from around 1 million to 2.5 million. This increase in people living in the city inevitably led to an increase in people dying in the city. Thus, the cemetery crisis began.

Grave diggers were known to exhume corpses and cremate them to free up space. Bones were scattered without regard; new bodies were placed in shallow pits with just a thin layer of soil to cover them. This desecration was not only unseemly, it was a danger to public health.

Parliament was forced to close the overflowing cemeteries of inner London and opened seven large suburban cemeteries between 1832 and 1841, known today as the Magnificent Seven.

In addition, the Necropolis Railway was opened in 1854 to transport people on their final journey via steam locomotive to the Brookwood Cemetery in leafy Surrey.

Whilst the railway company has since departed, you can still follow the route from Waterloo to Brookwood. Below is a suggested itinery, along with ODOjack’s notes on each stop along the way:

Stop 1 – 121 Westminster Bridge Road, the Old Station

The decision to open the London Necropolis Railway was not without its critics, with its combination of bereavement and efficiency. In 1842 the Bishop of London, The Right Reverend Charles James Blomfield, told a House of Commons selected committee “I consider it improper” and that train travel was “inconsistent with the solemnity of a Christian funeral.”

Others were more enthused by the idea. In his essay ‘Pomp and Circumstance: Archaeology, Modernity and the Corporatisation of Death’, George Nash described “the station being just far enough from normal commuters so as to be discreet”

The original line opened on 13 November 1854 and operated from close to Waterloo station. By the 1890s a new station on nearby Westminster Bridge Road had to be built to fulfil demand.

Whilst all traces of the original station have now disappeared, the Westminster Bridge station is still standing, having been converted into offices. You can still see the grand red-brick Victorian facade which was the first-class ticket entrance.

A short distance away is Newnham Terrace, the site of the passenger waiting room. Bodies were stored under nearby railway arches while waiting to be boarded.

Stop 2 – Head to Waterloo Station

The 23-mile journey to Brookwood would be completed in around 40 minutes. So one could travel to the cemetery, attend a funeral, go to the catered reception where you would be served ham and fairy cakes, and be home within a few hours.

Trains would leave at 11:40am a return to London by 3:30pm. I travelled on the 12:07 train from Waterloo that uses the exact route.

The journey rolled through what was considered ‘comforting’ scenery, through Richmond Park and Hampton court.

Stop 3 – Catch the train to Brookwood

Unique rolling stock was commissioned for the service, as it was felt that other commuters would be uncomfortable travelling in trains that carried the dead and the grieving. The carriages were fitted with leather straps to keep the coffins secure. The trains were sometimes referred to as the ’dead meat express’. At it’s peak, the train would carry around 2,000 bodies a year.

Unfortunately, ‘the dead meat express’ is no longer with us, but whilst travelling to Brookwood it is worth considering the original trains and the experiences of its passengers.

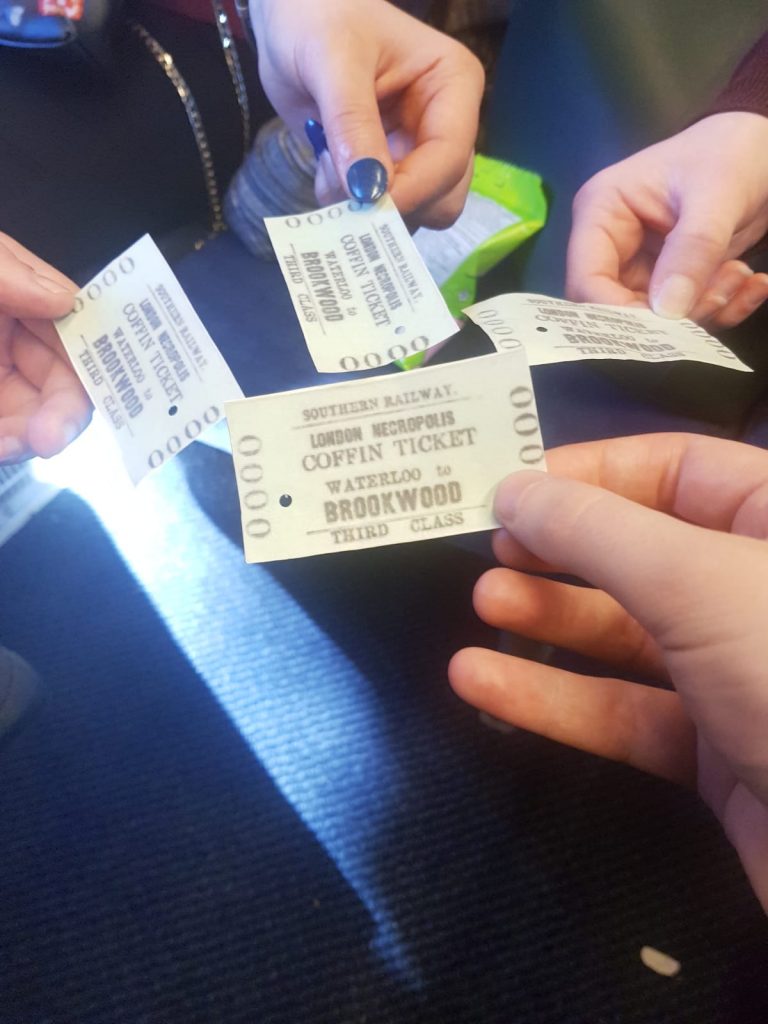

Fares were capped by the Act of Parliament and remained constant for 87 years, making the journey cheaper than other rail operators on the same route.

Live passengers were charged 6 shillings in first class, 3 shillings 6 pennies in second class and 2 shillings in third class for a return ticket (about £28, £16 and £9 today).

While dead passengers were charged £1 in first class, 5 shillings in second class and 2 shillings 6 pennies in third class for a one-way ticket (about £92, £23 and £12 today)

Today an open return ticket from Waterloo to Brookwood costs £16.60 off-peak and an anytime ticket costs £18.90.

The trains had carriages to allow mourners to travel with their loved ones on the way to the burial. They were separated by social class and religion in order not to offend Victorian morals, with a separate entrance for first-class mourners.

Even saying that, rich and poor traveling together, in the same way for this final journey, would have still been rather egalitarian for the time.

Stop 4 – Arriving at Brookwood Station

The station of Brookwood was described in 1904 by Railway Magazine as ‘the most peaceful station in the three corners of the kingdom – this station of the dead’ but also as ‘a sad station, the saddest in our islands.’

Originally, a branch line left of Brookwood station would have taken passengers directly to one of two stations in the cemetery: one for Anglicans and one for non-conformists and other denominations.

Whilst the original stations are no longer there, Brookwood station has kept its direct link to the cemetery. A subway from the station concourse will take you directly into the grounds.

Stop 5 – Brookwood cemetery

During the 87 years of the London Necropolis Railway operation 203,041 people were buried at Brookwood.

Brookwood was at one time the world’s largest cemetery. Wadi-us-Salaam (the Valley of Peace) in Iraq now holds this title, but Brookwood remains the largest cemetery in Europe.

The cemetery was designed to feel like a place of perpetual life. The cemetery was filled with evergreen plants like giant sequoia and redwood trees. The plan was to allow the cemetery to accommodate 28 million graves.

I visited on a bright clear warm February day and I have to say that I think the designers achieved this effect.

Around a third of the graves in Brookwood are unmarked. These pauper graves were paid for by the parish of London, but families were not allowed to erect any monument. Patches of nettles can be a sign of an unmarked grave as they grow on disturbed soil with higher level of decomposed materials, such as human remains.

One of the more notable residents of the site is the Anglo-Saxon monarch, Edward the Martyr. Edward’s remains were found in the 1930s, but disagreement between the brothers who found him meant he spent some time in a cutlery box stored in a bank vault in Surrey. Eventually it was decided he would be placed in Brookwood cemetery and he is now housed in an orthodox church on the site.

To the right as you exit the station via the cemetery exit there is a small section of the orignal track and a sign with a brief explanation about the railway.

Stop 6 – Brookwood Military Cemetery

Adjacent to the cemetery is the Brookwood Military Cemetery, the largest Commonwealth war graves site in the UK. Over 5,000 graves mark the final resting place of casualties from both world wars. The gravestones stand in regimented rows, stretching to the horizon and bearing mute testimony to the horror of war.

An extensive plot in the west corner of the military cemetery contains some 2,400 graves Canadians who died in the Second World War including 43 men who died of wounds sustained during the Dieppe Raid in August 1942. In addition to the Commonwealth plots, the cemetery also contains French, Polish, Czechoslovakian, Belgian and Italian sections and a number of war graves of other nationalities, all cared for by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Stop 7 – Back to Waterloo and time to consider the demise of the railway

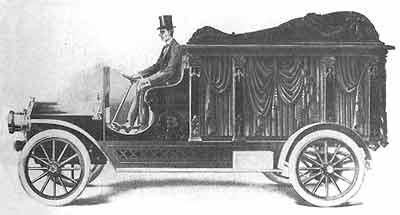

Usage of the railway began to decline with the introduction of the motor hearse in 1901, which by 1920 was a more popular means of carrying the dead than either the train or horse-drawn hearse.

But it was the Luftwaffe who hammered the final nail into the coffin of the Necropolis Company. During the night of 16–17 April 1941, in one of the last major air raids on London, the Westminster Bridge Road station was destroyed by falling bombs.

The Southern Railway offered the Necropolis Company temporary use of Waterloo station to allow the service to continue. This was however, on the proviso that they would not be allowed to sell cheap tickets to visitors travelling to and from the cemetery stations unless they were travelling to a funeral that day.

This meant those visiting the graves of loved ones had little reason to choose the Necropolis Company’s irregular and infrequent trains over the Southern Railway’s fast and more frequent services to Brookwood.

The London Necropolis Company attempted to negotiate a deal by which genuine mourners could still travel cheaply on the 11.57 am service to Brookwood (the Southern Railway service closest to the London Necropolis Company’s traditional departure time). But the Southern Railway management refused to entertain any compromise.

In September 1945, following the end of the war, the directors of the London Necropolis company met to consider whether they should rebuild the terminus and reopen the London Necropolis Railway. In mid-1946 the company formally informed Southern Railway that the Westminster Bridge Road terminus would not re-open.

Gone and forgotten, by all but a few. Just like many that it carried over the years.

Sources and Further Reading

https://londonist.com/london/history/this-london-building-used-to-house-a-death-railway-station

https://lookup.london/london-necropolis-railway/

http://www.planetslade.com/necropolis-railway1.html

http://www.coachbuilt.com/bui/c/crane_breed/crane_breed.htm

http://www.brookwoodcemetery.com/

https://www.discoveringbritain.org/activities/greater-london/trails/brookwood-cemetery.html