British parliamentary democracy has experienced a bit of a reputational downturn recently, but it’s still known around the world as the ‘mother of Parliaments’. One of the most iconic parts of British democracy is Prime Ministers Question Time (PMQs).

PMQs is a weekly opportunity for the Leader of the Opposition, and MPs from across political parties, to directly field questions to the Prime Minister. Odd Days Out has been to investigate how you can join in before the entire thing collapses in on itself.

History of PMQs

Like many aspects of British Democracy, PMQs is the result of an informal precedent only very recently acquiring a more formal arrangement.

For centuries, questions to the Prime Minister were asked and answered in the same way as questions to any other minister. Prior to 1881 questions would be asked when relevant ministers were available to attend parliament. There were no formal rules around these sessions and questions would be asked in whatever order MPs rose.

In 1881 parliament introduced fixed time limits for all sessions. Time was also set aside in parliament for the Prime Minister to answer questions. In 1953 Winston Churchill agreed that two slots each week would be set aside for asking him questions. These were fixed on Tuesday and Thursday of every week that Parliament was in session.

In 1959 the Procedure Committee (which is charged with making recommendations on the practices within the House of Commons) suggested that questions to the Prime Minister be taken in two fixed periods of 15 minutes each.

Following a successful experiment following these guidelines, PMQs was made a permanent arrangement in 1961. From then on the sessions have remained an immoveable fixture of parliamentary business.

PMQs Today

Currently PMQs takes the form of one half an hour session each week on a Wednesday at noon. This arrangement began when Tony Blair was Prime Minister and his successors have not sought to change it.

Six questions are allocated to the Leader of the Opposition (Jeremy Corbyn at the time of writing). This part of the session has taken on the appearance of a boxing match. The Prime Minister and Opposition Leader spar in a series of points and counterpoints.

Politicians are aware of the high-profile nature of PMQs. It’s keenly felt that a ‘victory’ in this sparring match retains some significance for the ‘winner’.

Once the Leader of the Opposition has asked his questions, two further questions are reserved for the third largest party in the House (at the time of writing this is the SNP).

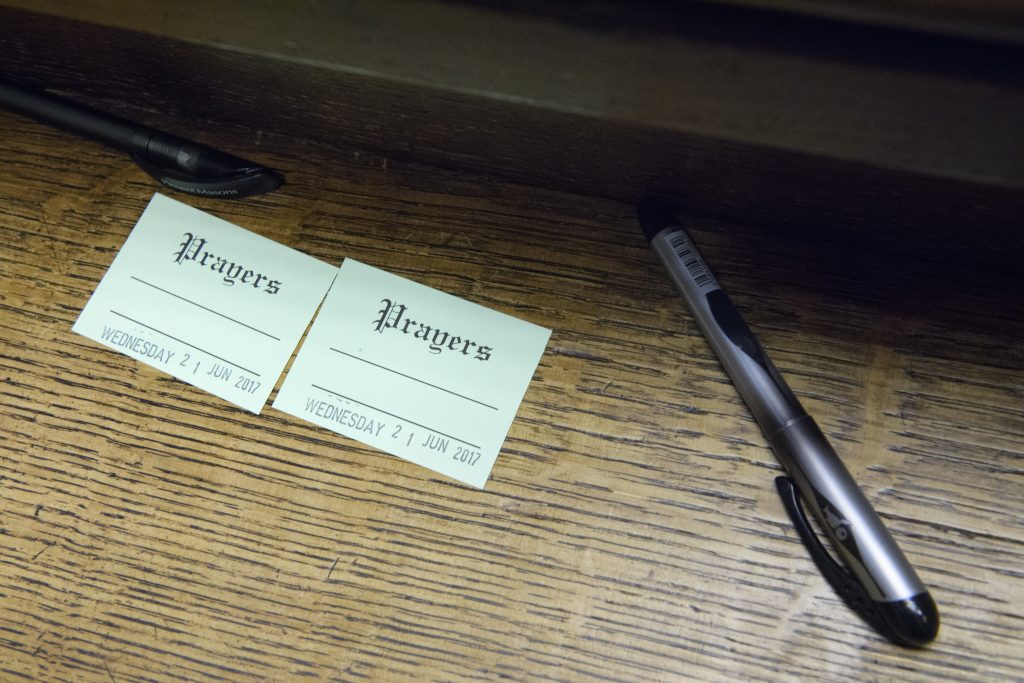

Then there is the balloted section of the session; lucky MPs who have entered the ballot get the chance to ask their own questions.

Getting Tickets For PMQs

Most people don’t realise that the House of Commons has a limited public gallery. Without fail, the gallery always fills up for PMQs.

Your first option is good old-fashioned queuing. A small number of tickets may become available on the day. However, parliament warns that there may be a 1-2 hour wait for these with no guarantee of success.

However, a limited number of tickets are offered to MPs. So your best bet might be (depending on your MP) to contact your local MP directly and appeal for tickets.

At Odd Days Out we were lucky enough to secure a ticket prior to the session. But we were warned we still needed to arrive an hour before the start.

Parliament has a strict security protocol and all visitors undergo a full airport style search. We were then ushered, via Westminster Hall, to Central Lobby, the grand chamber that sits between the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

From there we ascended the winding staircase to the public gallery above the chamber.

Viewing Experience

It is not always obvious where the public gallery is situated when watching PMQs on the TV. The camera angles conceal the upper floor of the chamber where members of the public sit. Indeed, this area only really comes to public attention when protestors manage to infiltrate the public gallery en masse.

Members of the public are normally sat in the gallery behind a window to prevent them from interfering with the politicians below. This affords a fairly good view of the main participants in PMQs, including the Prime Minister, Leader of the Opposition, and the Speaker. Should you stay for the supplementary questions from MPs, you may not be able to see those in the the darker corners of the back benches.

TV screens are helpfully provided to allow those in the gallery a chance to see the action a little closer. As well as this, there are speakers in the gallery which broadcast the microphoned cacophony below. So even if you cannot directly see what is going on, you will have a chance to hear everything.

Worth a Trip?

Although the process of securing tickets for PMQs can be a bit of a faff, it’s certainly worth the effort for anybody still interested in politics in the UK.

It is worth it alone for the chance to see the venerable institution of the House of Commons in action, even if you may not be a fan of many of the main characters in the drama.

With the exception of Westminster Hall, photos cannot be taken when visiting Parliament. As such, the photos for this article have come from the UK Parliament Flickr Feed and are used under Creative Commons License