A Historical Footnote – visited by ODOstefan and ODOmatt on the 12th November 2017

Whilst the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 is the most well known of the popular uprisings in Medieval England, the Jack Cade rebellion of 1450, an important precursor the the War of the Roses, is worthy of much more attention.

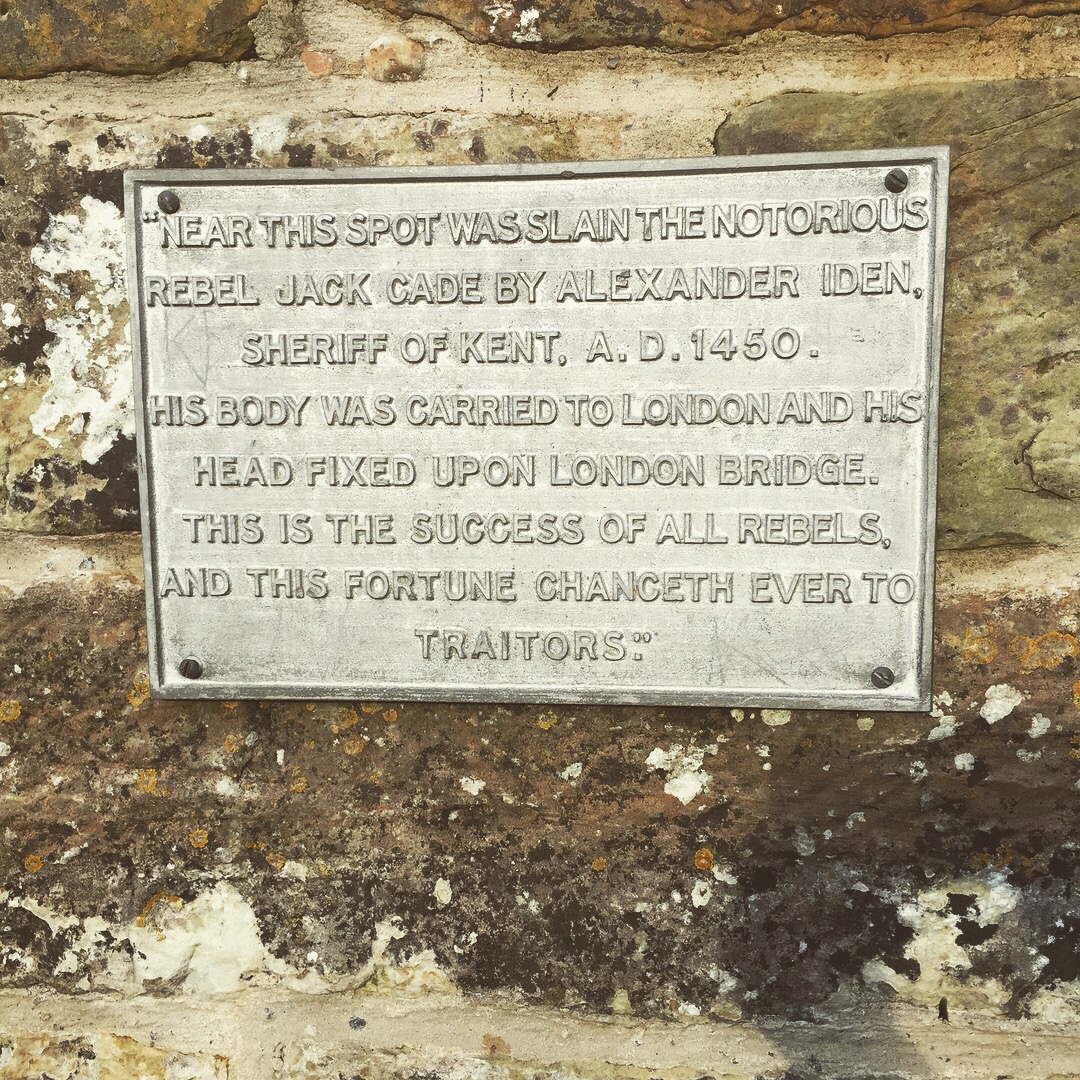

Despite the claims of this Grade 2 listed monument, there is little evidence to suggest ‘notorious rebel’ Jack Cade was actually ‘slain’ in Cade Street, but given that the town has based it’s entire identity around this claim it’s probably best not to mention this to any locals.History

By 1450 the Hundred Years’ War was 113 years in and surely many of the people of England must have been feeling it had been going on for at least 13 years too long. English success at the Battle of Agincourt was 35 years in the past. Cressy and Poitiers distant memories. The peace that had been hoped for after the marriage of Henry VI to Margaret of Anjou was shattered when fighting returned in 1449 after an English force sacked Fougères before a reinvigorated France quickly took hold of Normandy.

Faced with the impending loss of the war with France, the Commons and the wider public were searching for someone to blame – they were out for blood. Their target: William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk. Suffolk was seen as responsible for both the military and diplomatic failures which saw a large part of France given back to the French for a weak and ultimately failed peace treaty.

A close friend and confidant of the King, Suffolk managed to escape execution and was instead sent into exile. Those manning the ship tasked with exiling Suffolk had other ideas, a mock trial ensued in which he was unsurprisingly found guilty and was subsequently beheaded.

When Suffolk’s decapitated body washed up in Dover rumor spread that the king was going to take revenge on Kent for their purported involvement by turning Kent into a ‘wild forest’ (Alexander L. Kaufman) . This fear combined with war weariness, economic hardships of the period and widespread corruption meant Kent was a tinderbox waiting for a spark to ignite the flames of rebellion.

Jack Cade and the Rebellion

Being from the lower ranks of society there is little documentation about the man who provided the spark for the Kentish rebellion, but it is thought Jack Cade was born sometime between 1420 and 1430 in Sussex.

Adopting the alias John Mortimor in an attempt to claim royal lineage and add authority to his cause, Cade proclaimed himself the ‘Captain of Kent’. Cade organised the commons of Kent and produced a manifesto entitled ‘The complaint of the poor commons of Kent’. The manifesto demanded an end to corruption, punishments for those advisors that had failed the king and for Kent to be spared the King’s wrath.

Cade and around 5,000 followers initially marched to the traditional meeting place of rebels, Blackheath. After defeating royal troops en-route near Sevenoaks the threat from this band of rebels became clear. Upon entering London the rebels were welcomed by the citizens; they proceeded to execute the archbishop of Canterbury along with Henry’s treasurer and the Sheriff of Kent, Henry Cromer.

After the rebels turned to looting and drunken behavior the citizens of London lost sympathy and a battle ensued on London Bridge. Cade was then persuaded to call off the rebellion on the understanding that pardon’s would be issued for those involved. Recognising that he was unlikely to be spared, Cade fled and was later captured and mortally wounded by Alexander Iden, a future Sheriff of Kent.

The killing of Cade by Iden is featured in Shakespeare’s Henry VI Part 2, highlighting the significance of the events preceding the War of the Roses. Interestingly, the location noted in the script is Kent, Iden’s Garden – not Sussex.

Location, Location, Location

Cade street’s claim to be the location for the capture of Cade seems to be widely accepted and repeated as fact without question in many places. There is however growing dissent from Kentish folk about this claim, but we needn’t prepare for another Kentish rebellion as it does seem to be contained to a few local history websites for the time being.

It is thought that Cade was apprehended near ‘Heathfield’, however it has been suggested that this has been confused with ‘Hothfield’ a village in Kent. Supporting this claim is a monumental inscription in Hothfield church which reads:

The Rebel JACK CADE, in ye Reign of HENRY 6, was here killed by One Alexander EDEN (or IDEN) a Gentleman of this County, who, for his Reward, was knighted, and received 1000 Markes

This transcription was noted in 1758, so it certainly existed prior to the erection the Cade Street monument. In addition to this, the History and topography of Kent volume 7, published in 1798 states that Cade was ‘generally supposed’ to have been captured in a parish neighbouring Hothfield, it goes onto say that many believe he was captured in a field in Hothfield known to this day as Cade’s field – no mention of Heathfield or Cade Street.

The final piece of evidence, which for me swings the debate in Hothfield’s favour is that Alexander Iden, the future sheriff of Kent who slayed Cade, was a landowner in or near Hothfield. This matches up with the notes in Henry VI, Pt 2 which state the events took place in Iden’s garden.

The debate generally seems to be split along county lines, with Sussex historians claiming Sussex and Kentish historians claiming Kent.

As a Sussex native (though, not a historian) I am going to break with this mould and concede to Kent. If you have any evidence to indicate otherwise please comment below or email stefan@odddaysout.co.uk. If you can provide compelling evidence to the contrary, I would be happy to once again to take up the Sussex mantle.

The Monument

Francis Newbery of Heathfield Park, a publisher and businessman was erected the monument some time between 1791 and 1819.

Francis Newbery of Heathfield Park, a publisher and businessman was erected the monument some time between 1791 and 1819.

Mr Newbery’s attempt to commemorate the possible site of a historical event should of course be lauded. Unfortunately however, the monument itself isn’t particularly interesting – just your basic square stone plinth with a plaque.

A visit really can only be justified if you happen to be passing through. That said, a trip to the monument provides an opportunity to educate anyone that you have dragged along on the history of Jack Cade.

Getting there

The monument is located in Cade Street on the B2096, which runs from Heathfield towards Battle. Parking can be found at the Half Moon Inn, which is a 2 minute walk to the monument, which will be on your left hand side if walking towards Battle.

Sources and Further Information

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/middle_ages/hundred_years_war_01.shtml

Henry VI and Ashford’s Rebel: Jack Cade

https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/discover/london-stone-seven-strange-myths

http://orig.villagenet.co.uk/?v=cade%20street_east%20sussex

https://www.stitcher.com/podcast/medieval-archives/e/48441203

The complaint of the poor commons of Kent (Modernised): https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/halsall/source/1450jackcade.asp

http://villagenet.co.uk/history/1450-cadesrevolt.php

http://www.kentarchaeology.org.uk/Research/Libr/MIs/MIsHothfield/01.htm

Edward Hasted, ‘Parishes: Hothfield’, in The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent: Volume 7 (Canterbury, 1798), pp. 514-526. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-kent/vol7/pp514-526 [accessed 21 November 2017].

http://www.publicsculpturesofsussex.co.uk/object?id=122