Ancient covens, the Devil’s homemade soup and an ethereal Julius Caesar – when it comes to Sussex folklore few places have as many associated legends as Chanctonbury Ring.

Since the Bronze Age this curious earthwork has held great significance to both Sussex natives and invaders from distant lands. Risking the wrath of ancient spirits, Odd Days Out has been to investigate why, to this day, legends and rumours persist around the area.

The Chanctonbury trees

Chanctonbury Ring is a large mound set high atop Chanctonbury Hill, crowning it are countless beech trees. These trees are a relatively recent addition. The story behind them is integral to understanding both the historical significance and folklore of the site.

Sitting beneath the hill is Wiston House, which in the 18th Century was the seat of the Goring family. In 1760 Charles Goring, then a school boy, was overcome with an inexplicable desire to see Chanctonbury Ring capped with trees.

Charles planted the trees in the same year and every day walked up the hill to water them.

Many objected to the planting of the trees and the resulting change they made to the landscape. Charles proceeded undeterred; he wasn’t going to let a few complaints get in the way of his horticultural desires.

All was well for a time, but in 1786 a new owner lay claim to the land by the traditional process of ‘treading in’. Charles refused to budge. The new ‘owner’ made an offer to pay for the land but was confounded by Charles’ obsession with the Ring. Letters went back and forth and eventually the interloper conceded ownership. Charles won the battle and kept his precious trees.

Charles survived to see the trees mature and on his 85th birthday wrote a poem to mark the occasion:

Charles Goring’s poem for the trees

How oft

around thy Ring, sweet hill

A boy, I used to play

And form my plans to plant thy top

On some auspicious day…

… And

then an almost hopeless wish

Would creep within my breast,

Oh! could I live to see thy top

In all it’s beauty dress’d

That time’s arrived; I’ve had my wish

And lived to eighty-five;

I’ll thank my God who gave such grace

As long as ere I live.

Historical Significance

Despite Charles’ best efforts, his trees would not take root in the centre of the ring. Years later, research into this anomaly led to the discovery of a Roman temple, just inches below the surface.

It was known that the site had ancient links: in the early Iron Age, the outer edge of the ring marked the walls of a fort. But, the temple was a revelation.

To the South West of the ring is another temple. This was constructed around the same time in a similar style, but with a strange pointed design. This building has never been excavated and remains a mystery.

These were the first of many discoveries assisted by the trees.

During replanting in the 1970s, an excavation took place. Archaeologists discovered Neolithic flint work and Bronze Age pottery, indicating the site was older than previously thought.

In October 1987, England was hit by a ‘Great Storm’ and the Ring was stripped of its trees. Exposed beneath the torn tree roots were the leg bones of an adult male, dating from 960-1280 AD. In addition, large quantities of pig bones were found – possibly sacrificial offerings.

Curiously, despite the rich history of the site, little evidence of settlement has been found. Given the reuse of the encampment for a Roman temple, archaeologists believe this is likely due to it being a ritual centre.

Folklore

Given its history it is no wonder that legends have cropped up about the site. However, the sheer amount of these tales is peculiar. One theory for this is that the Roman Temple may have been devoted to the god Mithras.

The Cult of Mithras is a topic we covered in detail a previous article (The London Mithirum); but in summary, small groups of worshippers met in cave like temples and underwent various ordeals in the name of Mithras.

This cult came to prominence at the same time Christianity was gaining acceptance. Early Christian propagandists attacked Mithratic temples and spread rumours about the goings on at their places of worship.

Long after the temples were lost, tales of these strange places continued to be passed down through the generations. As is the way with oral storytelling, the stories were adapted to meet the current fears of the times.

As a result, these places were imbibed with legends. If Chanctonbury Ring was indeed once home to a Mithratic temple, it would go some way to explaining the cacophony of stories told about the place.

You can find a good summary of these tales at the Sussex Archaeology page on Chanctonbury Ring. However, Odd Days Out has also picked a few of our favourite tales to highlight below.

Summoning the Devil & friends

Not far from the ring is Devil’s Dyke – a deep V-shaped valley near Brighton. Legend has it that the devil, furious that Sussex had converted from Paganism, dug the dyke himself. The Devil heaved clods of earth and threw them over his shoulder. Upon landing, these clods created land masses across the south-east, places such as the Isle of Wight and numerous hills – including Chanctonbury.

Given this, you can of course find Beelzebub at the Chanctonbury clod. To summon Satan, simply walk round the hill seven times, he will then offer you a delicious bowl of soup (or sometimes porridge) in exchange for your soul.

However, if you only walk around the mound three times, a lady on a white horse will appear instead.

Understandably, the dark lord isn’t to everyone’s taste. If you wish to summon someone a little less threatening, simply recite ‘A midsummer night’s dream’ to meet the fairy-folk.

Also rumoured to make the occasional drop-in is a Saxon killed in 1066 and a druid looking for buried treasure.

Counting the trees

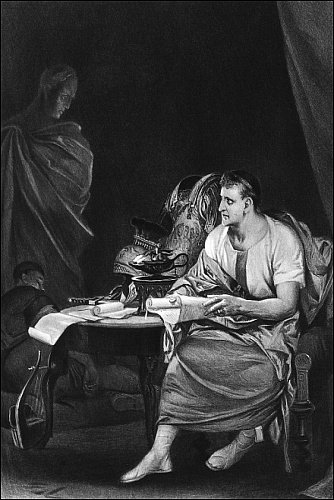

The trees planted atop the ring have deep roots that invade the ancient roman temple. It is said to be impossible to count all the trees on the hill. Others say that counting the trees will summon Julius Caeser and his army.

Odd Days Out are yet to find a satisfactory reason why Caeser and his army would be hanging out on a hill in Sussex. Disappointingly, other than this legend, nothing seems to link Caeser to Chanctonbury.

Witchcraft, Druids & the Occult

Famed occultist Aleister Crowley and his disciple, Victor Neuberg of Steyning both considered the ring to be ‘a place of power’. Neuberg’s poems describe youth’s being burnt alive as part of Druidic sacrifices within the ring.

Adding further to the Druidic links is Sixteenth-century astrologer and druid Prince Agasicles Syennesis. The prince whiled away his evenings wandering around the ring staring at the stars. Then, one day, he was unexpectedly found dead in the ring. Next to his corpse, written in charcoal, the words “Sepeli, ubi cecidi” (“Bury me where I have fallen”).

The ‘mother of modern witchcraft’, Doreen Valiente, claimed the ring was the meeting place for an ancient coven. In 1979 Chanctonbury hit the headlines when a witch alter was found in the ring. The alter was a 5-pointed star made of flints within a circle of flints. Tales of witchcraft are however, a more modern addition to the folklore of the site.

Visiting

Situated as it is at the top of Chanctonbury Hill, there is going to be a bit of a walk to visit the mysterious ring.

The Chanctonbury Car Park and Picnic Site (BN44 3DR) is the best place to start your walk. Arrive in good time as the site is popular with dog walkers and only a few parking spaces are available.

Below is the 3.7 mile route planned by Odd Days Out. Also on this map is a shortcut for those in a hurry, however this is a much steeper path.

Once parked up, you will quickly notice the large wooded hill you are about to climb. From the relatively flat surrounding, the prominent peak stands out proudly.

The start of the route takes you along the base of the hill and from here you can begin to sense the atmosphere of the place. To your left elevated looming trees set amongst wilderness, to your right tranquil managed-countryside. This contrast will continue until you turn and head towards the peak.

Stunning views of the Sussex countryside greet you as you step onto the summit plateau.

Drawing your gaze away from the view, you will notice that the tree cover, which had surrounded you, has gone. Looking further down the path you will see Chanctonbury Ring, its beech trees prominently sticking out of the clearing.

Approaching the raised earthworks, you can begin to sense the eerie atmosphere infused into the site by generations of story tellers.

Spend some time here wandering through Goring’s trees. If you are brave enough, try to count them – or if you desire a bowl of soup, just run around the ring seven times.

Sources and Further Information

Sussex Archaeology: http://www.sussexarch.org.uk/saaf/chanctonbury.html

https://office23.jimdo.com/antiquities/hill-forts/chanctonbury-ring/

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:Highways_and_Byways_in_Sussex.djvu/174

The A-Z of curious Sussex, Wendy Hughes

Sussex Folklore, Jacqueline Simpson

Curious Sussex, Mary Delorme

Hidden Sussex, Warden Swinfen & David Arscott

People of Hidden Sussex, Warden Swinfen & David Arscott

Sussex Villains, W.H. Johnson