Located on the Denge marshes on the Dungeness Peninsular in Kent, lie three vast concrete structures, rising out of the flat landscape like relics from some long-forgotten ancient civilisation. They are the Sound Mirrors, a pioneering attempt to create an early-warning system to detect incoming hostile aircraft. Odd Days Out has been to investigate.

Terror from the skies

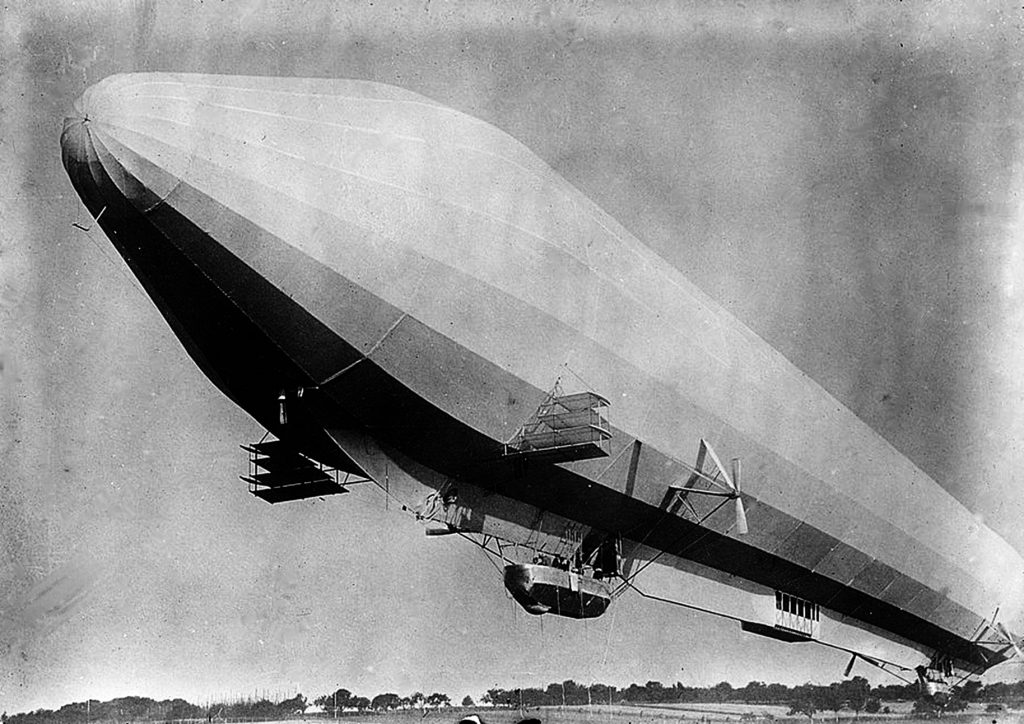

On January 19, 1915 an event occurred which would change warfare forever. Two Zeppelin airships flew across the channel and dropped bombs on Great Yarmouth, Sheringham and Kings Lynn. Four people were killed and several buildings were damaged.

A new and deadly terror gripped the country. The war had reached out beyond the battlefields of western Europe and into people’s homes. Total warfare had arrived.

The Tucker Microphone and the beginning of acoustic detection

As planes replaced the cumbersome airships, the raids became more deadly and it was clear that something had to be done to tackle this new fearsome menace.

The idea of tracking an aircraft acoustically was based on technology already being used on the western front. Prior to any offensive, the enemy would unleash a massive artillery barrage from behind their lines. If those guns could themselves be accurately targeted, the operation would probably fail. So researchers worked on a way of listening for the sound of a gun from various points and then triangulating the guns’ position.

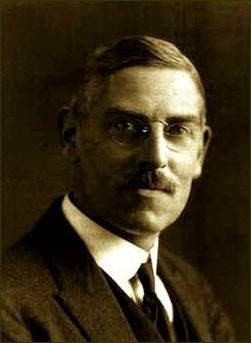

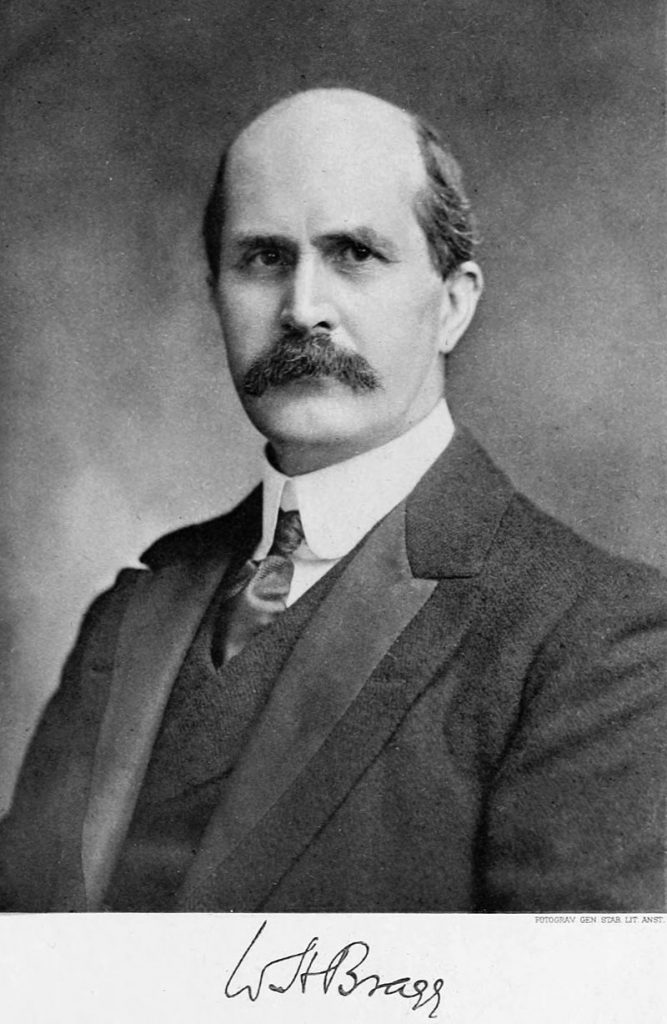

Under the guidance of Lieutenant William Bragg, who had shared a Nobel prize with his son in 1915 for their work on X Rays, acoustic detection became an effective weapon against German artillery. In June 1916 another Lieutenant, William Tucker, invented the Tucker ‘hot wire’ microphone which essentially used a thin wire to measure the cooling effect of the shock wave of the gun firing to give a precise reading. The advantage of the Tucker microphone was that it eliminated all background noise such as rifle fire or of the shell travelling at a high velocity through the air.

As the system developed, it became increasingly accurate and was able to locate enemy artillery accurately to within 25 meters. The Tucker microphone would be central to the development of acoustic early warning systems and the sound mirrors of Denge.

The race to protect us from the enemy above

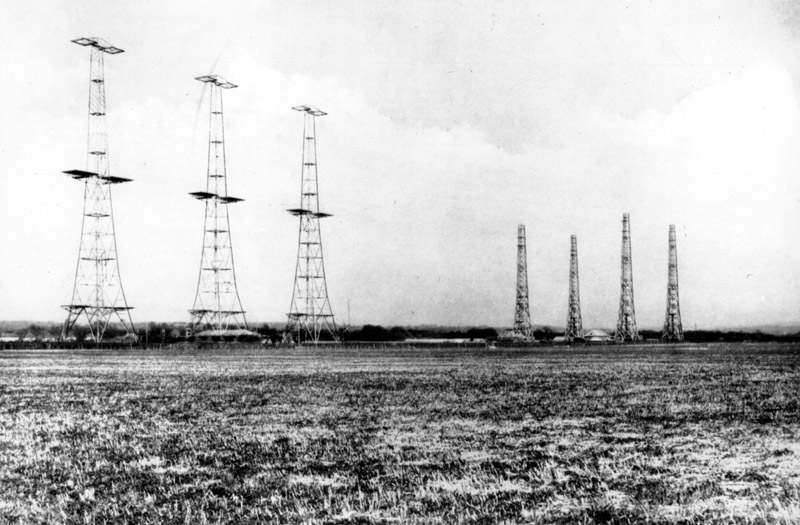

After the end of the first-world war it was clear that the Channel was no longer a reliable defence against enemy bombers. In response, the Air Defence Experimental Establishment was created in 1923 under the leadership of William Tucker. It conducted research into acoustical devices, searchlights and, from 1936, radar.

The War Department railway

Visitors to Dungeness today will be aware of the world famous Romney, Hythe and Dymchurch narrow-gauge railway. Opened in 1927, it carries thousands of tourists each year along Kent’s south coast. However, not many will know of a now-disused War Department Branch which left the track between New Romney and Dungeness and went out onto the Denge marshes. Opened in 1928 it carried materials and men to build the sound mirrors of Denge.

The Denge Sound Mirrors

Built between 1928 and 1935, the sound mirrors are made up of three giant concrete structures, managing to look both ancient and futuristic at the same time. Today, all three are designated as Scheduled Ancient Monuments, meaning they are of international significance. They formed just one part of a series of acoustic structures built around the country including one at Dover.

The mirrors were effective. Sound waves were caught in the centre of the mirror by a Tucker microphone and then relayed to an operator who would pass on information to a central command post. At the time of their construction this gave a fifteen-minute warning of an attack so that defences could be deployed. Of course, as modern aircraft became faster this warning time became shorter and less effective.

Radar

The development of radar was key to defeating the Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain and the Blitz. But this does not mean that the work on the sound mirror was a “dead-end technology” as some have suggested. Although the effectiveness of radar brought an end to the development of acoustic early-warning systems, it relied on the systems put in place for the sound mirrors to quickly pass on the information on incoming aircraft to a central command.

Visiting the mirrors today

Today, the area around the mirrors is owned by the RSPB and is an important ecosystem. It is home to marsh harriers and great white egrets. Although access is understandably tightly controlled, it is still possible to get quite close without disturbing the local wildlife. But to get right up to these amazing structures it’s best to wait for one of the RSPB’s open days.

I first saw the mirrors when we parked at the back of a holiday park, clambered over a fence and walked along a shingle causeway. As you round a corner there in front of you, looming out of the trees, is the larger of the two concave concrete dishes. Built in 1929 the 30ft mirror is an extraordinary sight.

Quarrying has changed the landscape dramatically since the dishes were built. The mirrors are now surrounded by lakes which adds to the beauty of the scene. A swivel bridge is kept locked shut to prevent you from accessing the site and disturbing the wildlife.

Open days

Our second visit was on one of the RSPB’s open days, when the bridge was opened. The 30ft mirror is even more impressive up close and is in good condition considering its age. Its concrete construction is oddly beautiful and futuristic looking.

The 20ft mirror is just behind and was the first to be built on the site in 1928. Despite the graffiti it is again an extraordinary structure.

As you pass the second dish you come to the largest structure of the all – the 200ft mirror. A wall of concrete stretching away in a beautiful curve.

A memorial to those who still keep us safe

Today, sophisticated radars and computers keep our skies safe as thousands of aircraft fly across Britain every day. The sound mirrors are a fitting tribute to those pioneers who helped develop the systems which enable us to fly in safety.

Getting there

Please note that access to the site is across a shingle causeway and is difficult for buggies and wheelchairs.

Because the mirrors are on an island, it’s best to access them on one of the open days. These are run several times a year between August and December. For more details visit the RSPB’s website here. There are usually guided tours giving more of the history of this fascinating site.

But it is possible to get to see the mirrors anytime without disturbing the wildlife by going as far as the swing gate. The easiest way to do this is to park at the back of the Romney Sands Holiday Park, The Parade Greatstone, Kent, TN28 8RN. Walk down the bank and onto the shingle causeway.