Prior to the invention of refrigeration, fresh food would either have to be eaten immediately or preserved in a way that would impact its flavour. With the invention of the ice house, also known as ice wells, the residents of Mari (an ancient city in modern-day Syria) came up with a solution to this way back in 1780 BC.

Britain was a little slow on the uptake: putting up with pickled, cured and rotten meat for a few millennia longer than necessary. Finally, in 1619 AD, James I commissioned Britain’s first ice house in Greenwich Park.

What is an ice house

Often found on country estates or associated with large mansions, ice houses were usually located near to a lake or other source of water.

Individual ice houses differ in appearance, but generally have a porch like entrance attached to a large dome. Much like an iceberg, the majority of the structure is located below the surface. Entering through the porch of an ice well, you would soon find yourself looking into a deep brick-lined pit where ice would be stored. At the bottom of the pit would be a drain hole leading to a lake or pond, allowing the melting ice to trickle back to its watery home.

Prior to the arrival of the ice house in Britain, rudimentary ‘ice pits’ had been used for food preservation. However, ice houses stepped up efficiency dramatically. The combination of the domed structure and its subterranean location allowed ice to stay frozen for up 18 months.

For the early British ice house, ice would be taken from a nearby water source in winter, placed in the well and insulated with straw. In some locations, special shallow ice ponds were built to make it easier for servants to garner their frozen harvest.

The Ice House Cometh

So useful was this innovation that ice wells started to pop up everywhere. Whilst it is difficult to know how many were built in total, around 2,500 are thought to still exist.

In the 18th Century, everyone began jumping on the ice house wagon.

No longer just a preserve of the royalty, they became popular with the gentry and well-to-do. A gentleman without an ice house would surely have been shown a cold shoulder by his contemporaries.

Entering the 19th century, having access to ice in the summer had become as essential as coal in the winter.

Britain began to struggle to produce enough ice to fulfil its needs. Thus, the Anglo-Norwegian ice trade was born. By the end of the century, Norway would be exporting more than a million tons of ice a year across the world.

Not only did this solve the shortage, it also provided ice of a much higher quality – in 1905 the Lancet, proclaimed Norwegian ice to be “pure, sparkling, and clean” and added that “no harm is likely to accrue” from its use.

When British pond water was used, it would have been unthinkable to add ice to your cocktails, make ice cream or plunge blanched vegetables into ice water. Norwegian Ice made everything a bit more palatable.

A cold wind blows

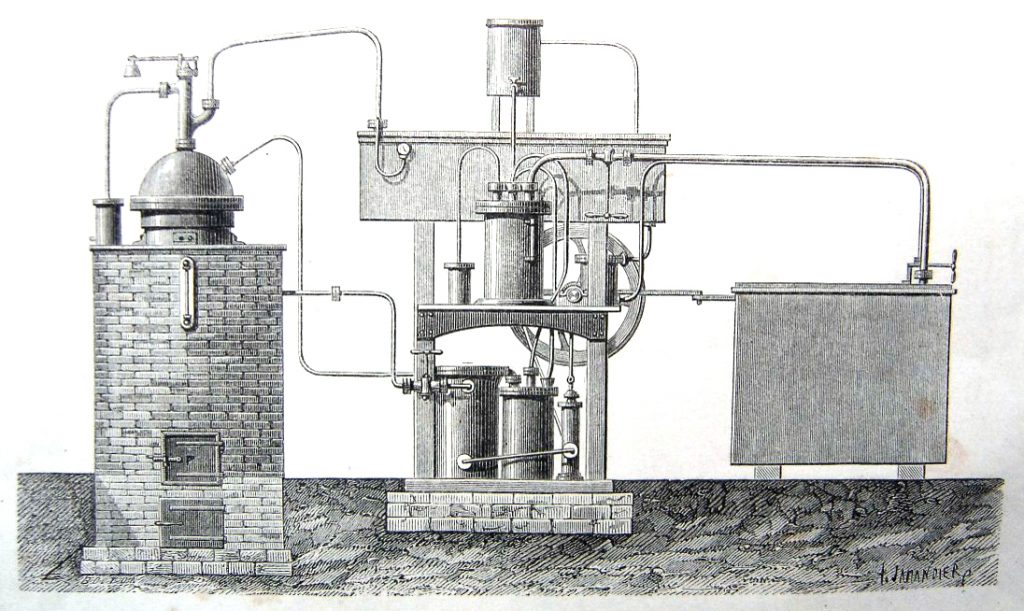

As well as the Norwegians, scientists and inventors also joined the cold gold rush. In 1842, American Scientist, John Gorrie created a system capable of refrigerating water to produce ice. Whilst a commercial failure, it inspired many others, including one Ferdinand Carre who produced a simple and relatively small ice making machine.

When the ice trade was disrupted in parts of America during the civil war, Carre’s machine became popular. It wasn’t long before the use of these machines spread across the pond.

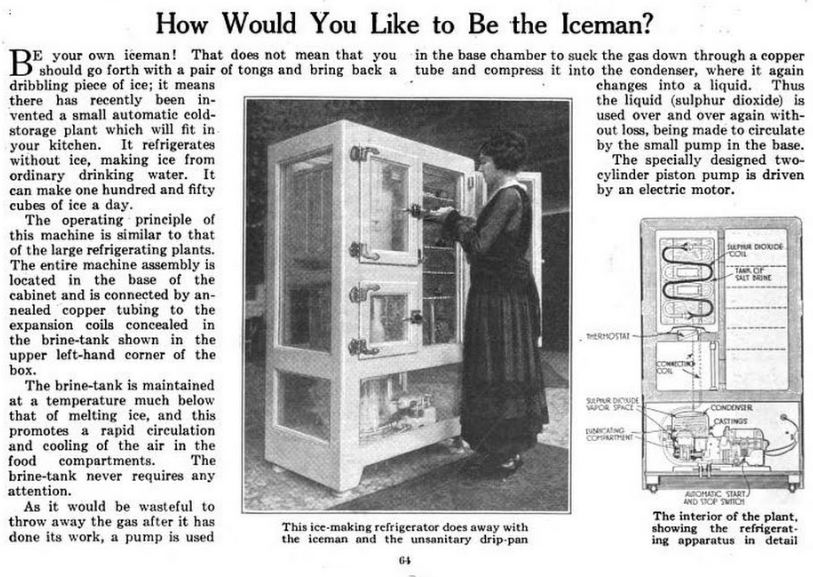

Following a 19th Century equivalent of Moore’s law, these machines got smaller and cheaper. Eventually, it became possible to provide refrigeration at home – without the need for big chunks of ice. In 1911 General Electric released a household refrigeration unit powered by gas.

The ice trade trundled on, but the cracks were showing – by 1920 Norwegian ice exports were 5 per cent of the levels in 1910.

Both the ice trade and the ice house had been rendered obsolete.

Much like the redundant giant gas holders we still see across Britain today, these once integral components of infrastructure have left a mark on our landscape. Whilst the visible part of an ice house was often knocked down, the deep well would usually just be boarded over or filled in – people still occasionally find great caverns hidden under their property.

Visiting

The Odd Days Out team were disappointed to find that the Greenwich Park ice house – Britain’s first, has been lost. Presumably a deep pit exists somewhere on the grounds, but no one is quite sure where.

Disheartened, but not discouraged, we set about finding another ice house within the Royal Borough of Greenwich. Fortunately for us, a short journey away from Greenwich Park is ‘The Tarn’, a beautiful landscaped garden-cum-bird sanctuary that once formed part of the grounds of Eltham Lodge.

The Tarn contains an interesting ice well dating to 1760. This was once used by staff working in the kitchens of Eltham Lodge. A segment of the dome is cut away, allowing visitors to peer in and marvel at the brick lined well.

For those wanting to really delve into ice houses, the London Canal Museum located in King’s Cross is the place to go. This ice house has been opened up and lit. The museum occasionally offers a tour that allows you to enter the ice well. In addition, they have set up an ‘ice well camera’ which visitors to their website can control: http://www.canalmuseum.org.uk/ice/icewell-camera.htm

These are just two of the supposed 2,500 ice wells located across the country – disappointingly, locating your local ice well is a bit of a task. No easily accessible catalogue of these sites seems to exist – this is something that Odd Days Out would like to change:

The ODO ice house database

As an Odd Days Out side project, we are looking to gather information on British ice houses – recording their location, date of construction and whether or not they are available for the public to visit. With this information we hope to be build a definitive map of ice wells for fellow Odd Day Outers.

Historic England have kindly provided us with their data on around 500 listed ice houses. Odd Days Out have also made enquiries to Canmore in Scotland and RCAHMW in Wales about adding their data to the map.

The data we have gathered so far represents less than a quarter of the 2,500 ice houses that supposedly still exist.

We want to find Britain’s missing ice houses. If you have any information on the location of an ice house, any information on those already on our list (including photos), please comment below or send an email to icehouses@odddaysout.co.uk

We have also set up a special page on the website for this project – odddaysout.co.uk/icehousedatabase

Current Listings:

Ice house hunters, please note: We do not know whether the ice houses listed above are accessible. Do not venture onto private property without permission. Be aware that ice houses attract bats – which are protected by law and should not be disturbed. Visiting an ice house can be unsafe, and Odd Day Outers do so at their own risk.

Sources and Further Information

http://www.lse.ac.uk/Economic-History/Assets/Documents/Research/GEHN/GEHNWP20-BB.pdf

http://www.canalmuseum.org.uk/ice/ice-wells.htm

http://www.london-footprints.co.uk/articehse.htm

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/europe/united-kingdom/articles/uk-ice-houses/